Where Human Rights Do Not Reach

Curated by Felicia Su, Sophie Tedesco, and David Zhu

December 2023

At the end of 2022, the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees reported a record number of 35.4 million refugees worldwide. During that same year, the National Institute of Corrections reported an incarcerated population of 10.35 million people, more than 2.2 million of which are in the United States.

In light of increasing individuals affected by statelessness and incarceration, “Locked In and Locked Out” seeks to highlight the limitations of modern interpretations of human rights with respect to these two communities. Though societies often view stateless and incarcerated individuals as opposite issues, one of involuntary displacement and one of punishment for criminal activity, this curation reveals the parallels in the violation of human rights committed against both populations.

Specifically, this exhibit explores the conditions of migrants and incarcerated people through a range of experimental mediums, from large-scale installations to portraits crafted with coffee and toothbrushes. Each artwork examines exclusion from normal citizenship in the abstract rather than through directed photographs: turning the voyeuristic gaze of academic institutions into a collection concerned with authentic experiences and open discourse. Stories are best told by the people who have lived them – Mostafa Azimitabar reflects on his detention as a Kurdish refugee through self portraiture, and Billy Sell used art as an act of protest against solitary confinement. We invite observers to actively participate in the exhibit by looking, questioning, and discussing the stories behind each piece.

As a whole, the exhibit underscores that the promise of human rights remains unfilled in the presence of people excluded from the privileges of normative political and social belonging. Refugees worldwide are locked out of their old nations and the opportunity to establish new citizenship, and locked in a system of displacement, evacuation, and asylum-seeking. Incarcerated people are locked into jails and prisons, and upon release, locked out of employment opportunities, housing, welfare, and civic participation. Both experiences exemplify the harm of denying a person the dignity of belonging. Through their art, the humanity of both stateless and incarcerated individuals shines undeniably, even to those who might refuse to recognize it.

Adrian Paci. Centro de permanenza temporanea (Temporary Detention Center), (still), Video, sound, color, 4:32, 2007.

A still frame from Adrian Paci’s 2017 Centro di Permanenza Temporanea (Temporary Reception Center), a short film named after temporary camps set up for illegal immigrants on the Italian coasts. The film depicts Mexican people climbing up an aircraft stairway in a Californian airport and explores the faces and expressions of individuals; no one is smiling.

Adrian Paci explores themes of dislocation and rootlessness as he draws from his own experience as a refugee who fled his native country Albania for Italy in 1997, driven by widespread social unrest and violent uprisings.

Centro di Permanenza Temporanea literally translates to Center for Temporary Permanence. The Italian government has since renamed its detention facilities as Centro di Identificazione ed Espulsione (Center of Identification and Expulsion) and most recently as Centri di Permanenza per i Rimpatri (Repatriation Retention Centers) as of 2017.

In 2023, the Italian government released a statement that asylum seekers would be detained in its facilities while their applications were processed unless they could pay 4,938 euros as a form of bail.

Refugees queue and wait on a stairway for a plane that never comes. In an airport, a hub of movement and transportation, geo-political systems deprive migrants of a destination. How do temporary receptions become permanent detentions?

James “Yaya” Hough, I am the economy, watercolor on paper, 2018.

I am the Economy, a watercolor painting by James “Yaya” Hough, an artist and former-inmate based in Pittsburgh.

Charged and convicted with murder at age 17, Hough served 23 years of a mandatory life without parole sentence. In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that life without parole sentences for minors are unconstitutional, and a subsequent 2016 case required states to apply the 2012 ruling retroactively. Hough was released from prison in 2019.

As an active participant in the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, Hough has completed over 50 murals in Philadelphia, State Correctional Institute (SCI) Graterford, and SCI Phoenix. He advocates for Decarcerate PA! and Project Lifelines in an effort to change the prison system in Philadelphia.

Hough makes his opinion of the US carceral system clear in his Project Lifelines profile: “The current system is surrounded in mystery because it cannot operate in sunlight. The current system consumes people and money – 50,000+ people and over 2 billion dollars annually. It knows no solutions except to grow larger.”

A man, a morgue, a machine. The prison system directly converts the forced labor of Black bodies into profit. Legacies of slavery are embedded in our modern criminal justice system. How do individuals enter this system, and why are generations trapped within?

Ai Weiwei, Laundromat, still image by Jeffery Deitch, 2016.

An image from Jeffrey Deitch of Ai Weiwei’s exhibit, Laundromat, displayed from November 5, 2016 to December 23, 2016 in New York City. The piece is composed of materials left behind – mainly shoes, clothes, and personal mementos – at Idomeni, a refugee camp on the border of Greece and the Republic of Macedonia.

Laundromat is part of an exhibition series created by contemporary Chinese artist Ai Weiwei that focuses on the plight of refugees. Ai began his project while under “soft detention” in China. As Ai first examined the experience of people forced to migrate, he could not leave China because the Chinese government confiscated his passport. Ai identified with the refugees’ experience of being viewed as subhuman.

Idomeni, the refugee camp Laundromat uses clothing from, consists largely of refugees fleeing war, primarily from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq. In March of 2016, Macedonia closed its border to refugees, creating a bottleneck at Idomeni and leaving around 15,000 people stranded there without resources to accommodate them. People lived in makeshift tents with no running water or sewage while heavy rains turned the area into a mudfield. Later that spring, Greek authorities forced many refugees to evacuate the camps, moving them to other locations in Greece, which many refugees feared would have worse conditions.

The refugees’ clothing tells the story of some of the trials of the camp and their journeys – mud splattered from the camps, soaked in sea water from the boat trip over. Ai says the goal of his art is to “testify to that refugees are human beings,” with remnants of their clothing humanizing a part of their stories.

To leave a state, to become a refugee, is to leave behind a life, a home, and an identity. The 2,000 printed media clips and photographs covering the walls and floor of the installation remind us that the world is watching this crisis unfold. But does it see the complete person who once wore these clothes?

Gilberto Rivera, An Institutional Nightmare, mixed media, 2012.

An Institutional Nightmare, a mixed media piece created by Gilberto Rivera in 2012 while incarcerated. Composed of federal prison uniforms, commissary papers, floor wax, prison reports, newspaper, and acrylic on canvas.

At 23 years old, Gilberto Rivera was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison on racketeering and conspiracy charges. Rivera is one of the approximately 33% of American men who will be arrested by the age of 23 (Brennan Center for Justice).

The loss of agency defines the experience of incarceration. This loss manifests not only in the lack of liberty while incarcerated, but in the lack of agency over one’s own life – inmates are often subjected to arbitrary transfers from prison, loss of visitation or rec time at the whim of a correctional officer, or unpredictable violence in carceral facilities. An Institutional Nightmare represents Rivera’s response to a hostile encounter with a guard shortly after Rivera saw his family for the first time in a decade. Rivera tore up an inmate uniform and prison papers, using floor wax from his sanitation job to solidify the artwork. The prison papers in the piece include commissary forms listing items such as underwear and regulated footwear, which the incarcerated people (or their families) must purchase at inflated prices.

Through his art, Rivera highlights the indignities of prison life, using his transfers to facilities around the country as an opportunity to find new artistic influences from the work of people in other prisons. Rivera ultimately reframed the constraints of prison as a medium through which he could express his creativity and humanity.

To enter a carceral facility is to become a prisoner, forced into an identity assigned by the state and conveyed through a uniform. Inmates rendered invisible by walls that separate them from their past-selves and the communities they once belonged to. Who sees them now?

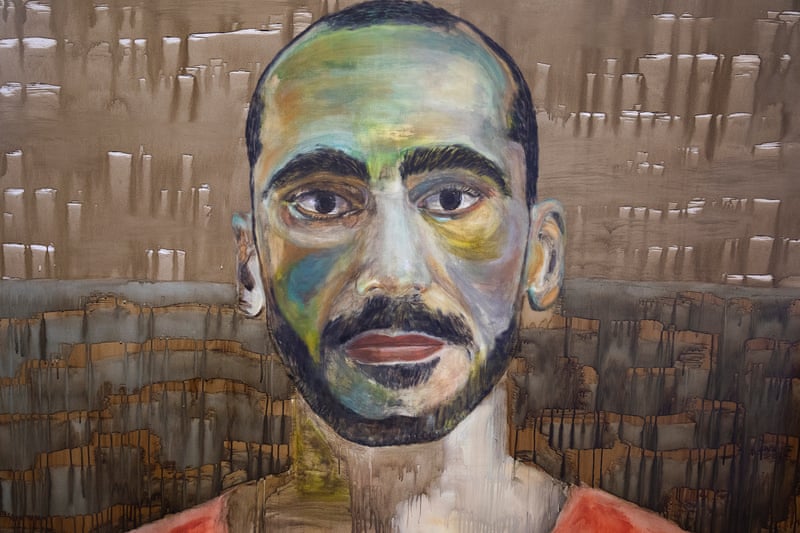

Mostafa “Moz” Azimitabar, Self-portrait, Coffee and acrylic on canvas, 190.5 x 191.8 cm, 2022.

A self-portrait created using coffee and toothbrushes by Mostafa “Moz” Azimitabar, a Kurdish refugee who spent almost eight years in detention, including 14 months in two Melbourne hotels.

Azimitarbar filed a lawsuit against the Australian government for his 14 month forced detainment. In a 2023 ruling, the Federal Court affirmed the Australian Government’s legal power to detain refugees in hotels for extended periods of time. However, the judge emphasized that the lawfulness of Azimitabar’s detention must not be confused with the morality of the issue.

During imprisonment, Azimitarbar used makeshift resources such as coffee and toothbrushes to create art. Though he drew this self-portrait after his release, Amzimitabar continued to use coffee and toothbrushes to create this artwork. In his words, “the coffee and toothbrushes are the small things [that represent] simplicity and resistance. They show I survived, they show I’ve continued.” Azimitarbar’s self-portrait highlights his personhood and functions as a form of resistance against the dehumanization of refugees.

In search of protection in Australia, Azimitabar instead suffered under governmental policies that burn billions of dollars to discourage refugees from exercising their right to seek safety and asylum. How does Azimitabar’s artwork function as a form of resistance against such injustice?

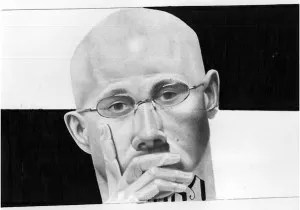

Bill Sell, Self portrait, 2013.

An installation (right) of a self-portrait (above) by Billy Sell (1976-2013), who served a life sentence for attempted murder and spent much of his sentence in isolation. Sell died during a statewide protest against solitary confinement in California prisons.

TW: suicide

Two weeks after the start of a statewide hunger strike in 2013 against long-term solitary confinement and related prison conditions, Billy Sell committed suicide while in solitary confinement. Sell was in a “Security Housing Unit,” a single cell with little to no contact with other people, since 2007 for murdering his cellmate.

A report regarding the 34 suicides in California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation facilities in 2011 found that:

- 24 of 34 (70.6%) committed suicide in single-cell status

- 20 of 34 (61.8%) had a history of suicidal behavior

- 30 of 34 (88.2 %) had a history of mental health treatment

Data has consistently evidenced disproportional rates of suicide and mental illness caused by solitary confinement. Despite the well researched negative impacts of solitary, the practice of solitary confinement continues to impact inmates – a study in 2019 showed that at any given day, over 120,000 individuals are subjected to solitary confinement in the United States.